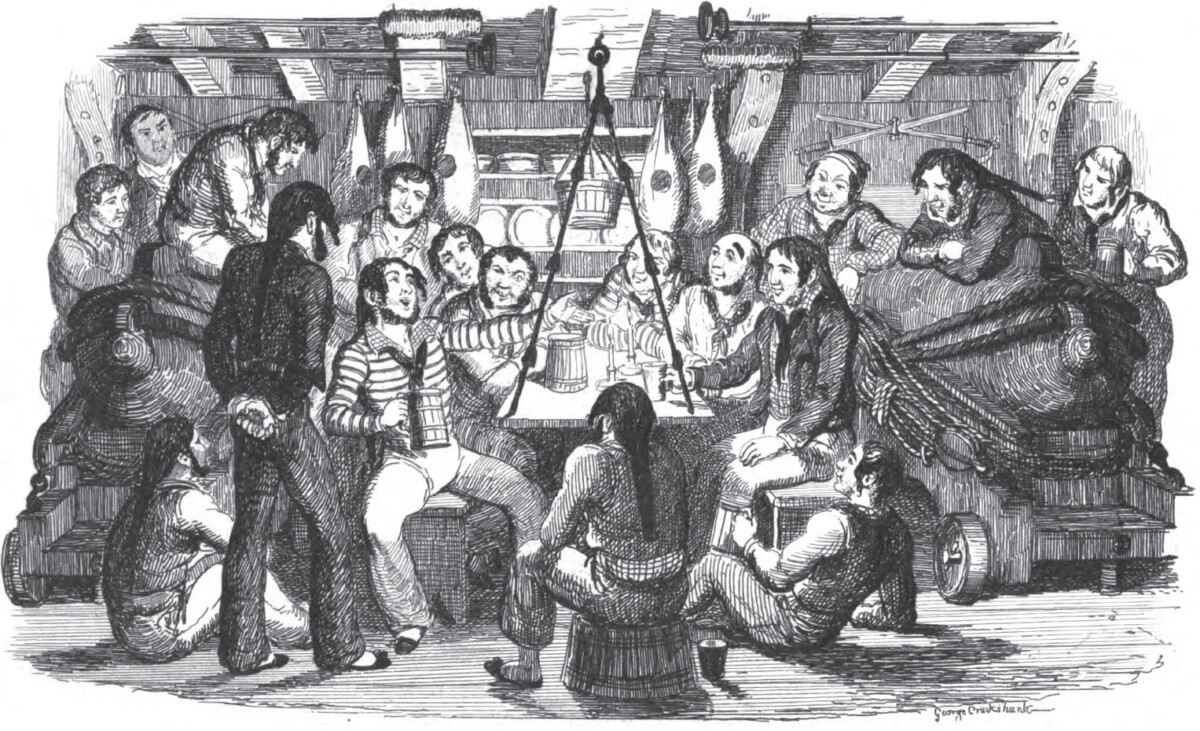

By George Cruikshank – Illustration “Saturday Night At Sea” from “Songs, naval and national, of the late Charles Dibdin; with a memoir and addenda.”, Public Domain

On Saturday 21st September, venues across the city will be hosting the Bristol Sea Shanty Festival. The festival always brings a joyous crowd to Underfall Yard, and it’s clear that sea shanties still have a hold over modern audiences. Volunteer writer Elaine explores the origins of the sea shanty and its lasting popularity. Does your favourite tune count as a “shanty” or a “sea song”?

In December 2020, when the country was in lockdown and Christmas was about to be cancelled, a Scottish postman went viral with a song about whaling. Nathan Evans’s TikTok cover of “Wellerman”, with its jaunty tune and singable chorus, sparked a sea shanty craze that earned its own hashtag, #ShantyTok. The song tells of an epic struggle between a whale and the crew of a whaling ship. The Wellerman was the provision merchant who brought supplies to the men marooned on whaling stations for months on end, longing for the luxuries of “sugar and tea and rum.” It caught the mood of a public isolated at home and in need of cheering up.

Despite the hashtag, “Wellerman” is not in fact a shanty. It is a sea song, or forebitter, something sung by sailors for entertainment in their free time. Shanties are work songs.Their purpose was to synchronise the heavy labour of crewing merchant ships in the days of sail. They were led by a shantyman. He sang the verse, the crew responded with the chorus, fitting the heaving and hauling to the rhythm of the song. A good song was “worth ten men on a rope.” It served “to cheer the soul, curse the [officers], mark the beat and lighten the labour.”

A shanty needs a strong chorus and a flexible approach to storytelling. “A good shantyman was never short of a verse”; upwards of thirty verses have been recorded for “Blow the Man Down.” If he ran out of material he would improvise around incidents from the voyage or the doings of his shipmates, usually to their discredit. Favourite themes included sailors’ adventures, or misadventures, with ladies of the town, the more innuendo or downright filth involved the better.

Raising the anchor at the start of a voyage called for a capstan shanty such as “Randy Dandy O.” In this “outward-bounder” the ship is heading for the dangerous passage around Cape Horn to Valparaiso on the coast of Chile. The shantyman cheerfully abuses his crew of “parish-rigged bums.” They seem a little ill equipped for such a perilous voyage, since “Our boots and our clothes, boys, are all in the pawn.” After fond farewells to the girls on shore, they “man the stout capstan and heave with a will”, ready for the hard work and dangers ahead.

“Stamp and go” shanties were used when hauling a rope by marching forward along the deck. This needed a good “runaway” chorus, such as “What Shall We Do with The Drunken Sailor?” The shantyman suggests inventive ways of punishing or reviving the sailor in question. The boisterous chorus of “Way hey and up she rises”, and the endless scope for improvisation, mean that this shanty is still one of the most widely known today.

Another stamp and go shanty is” Roll the Old Chariot Along”. It starts, “A drop of Nelson’s blood wouldn’t do us any harm”. This refers to the gruesome fact that Nelson’s body was preserved in a barrel of brandy to bring it home after Trafalgar. Among the more printable things that sailors also felt wouldn’t do them any harm were a plate of Irish stew and a night on the town. Bristol shantymen The Longest Johns have extended the list to include such delights as a toastie on the grill, a freebie from the bar and another swig of gin.

Traditionally, the last shanty sung on a voyage, when bringing the ship up to the quayside, was “Leave Her Johnny Leave Her”. This was the sailors’ opportunity to air their grievances about the ship, the food, the skipper and the mate without fear of punishment. Expressing such views at any other time “was almost tantamount to mutiny.”

Bristol Sea Shanty Festival is back on 21st September.

Modern ships do not need much in the way of heaving and hauling. Shanties have lost their function as work songs, but they have survived because people want to sing them. The call and response form makes them ideal for audience participation. Their purpose was to bring people together, and nothing does that better than roaring out a stirring chorus.

It was this desire to sing together that made “Wellerman” such a hit. Other TikTokers added harmonies and instrumentation to Nathan Evans’s original post. Remixed versions were created, reflecting the way shanties have always been influenced by contact with different languages and musical traditions. Other contributors began posting shanties. People who knew nothing about the genre discovered that shanties were easy to learn and fun to sing. A virtual community of shantymen and shantywomen was formed.

Sea shanties have ebbed and flowed in popularity since the end of the tall ships era, but they have never gone away. ShantyTok has introduced them to a younger audience, ensuring there will be a berth for the shantyman for a long time to come.

Coming along to the Bristol Sea Shanty Festival? Find out more here…

This article was written by volunteer Elaine Clark and reviewed by Underfall Yard Trust. Click here to read more about the Yard’s volunteering program.

The Recovery and Reinstatement Project is now underway after the fire in May 2023. Click here to read more and find out how to support the project…